New tools needed to contain household indebtedness

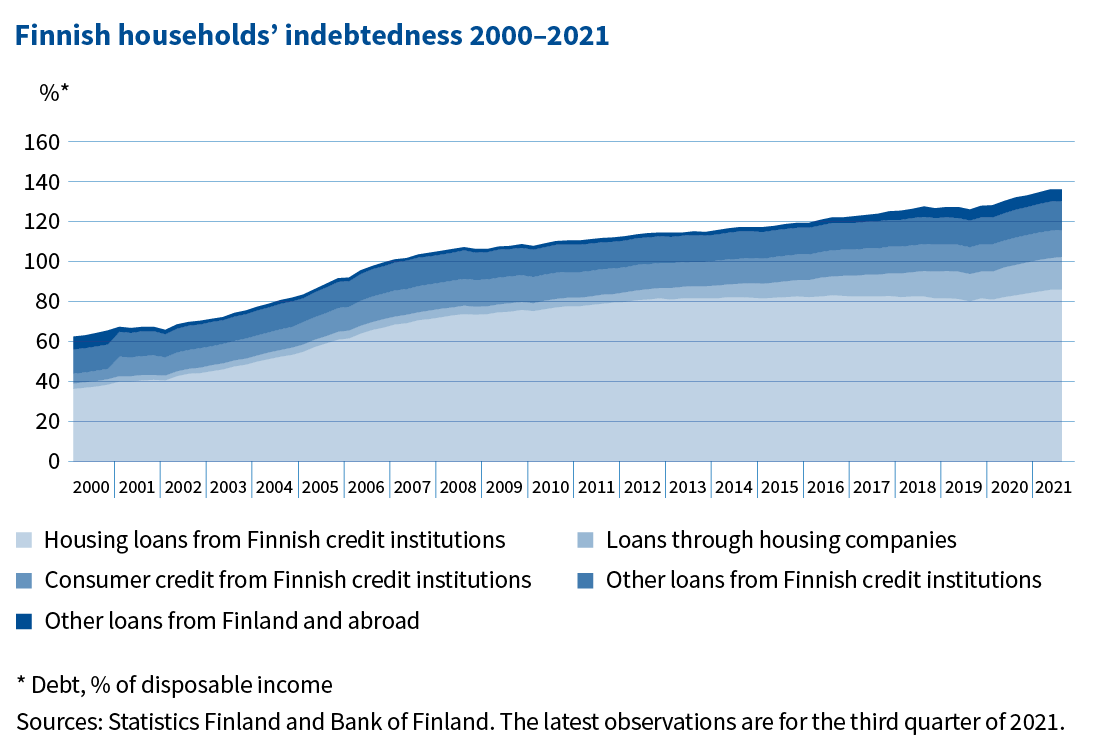

Household indebtedness has been rising for 20 years and currently stands at an all-time high: at the end of the review year, almost 400,000 Finns had a payment default on record. Over-indebted people or households are prone to protracted financial and social problems.

From the perspective of the economy, households’ over-indebtedness also weakens the capacity of the economy to adjust to adverse surprises. Highly indebted households may, for example, reduce their consumption when facing financial problems, such as unemployment, during a downturn. This in turn has negative impacts on the whole economy and companies’ activities. As consumption weakens and households’ debt burden grows further, banks’ credit losses may grow indirectly and with a lag. Credit losses, in turn, weaken banks’ capital adequacy and lending capacity.

The bulk of the household loan stock consists of housing loans. For the time being, the debt-servicing burden of households with housing loans has not increased significantly, as the general level of interest rates and interest rates on housing loans have remained very low for a long time now. Average loan periods have also lengthened. Household debt has been augmented not only by housing loans but also by consumer credit and indirect forms of indebtedness, such as housing company loans.

Macroprudential policy maintains financial stability

The objective of effective macroprudential policy is to maintain the stability of the financial system as a whole. It supports both conventional banking supervision as well as fiscal and monetary policies to achieve sustainable economic growth. The safeguarding of stability is contingent on three things:

- financial institutions’ adequate risk buffers

- the possibility to tighten the requirements in an upswing to prevent the growth of risks and vulnerabilities, and

- the possibility to ease the requirements in times of crisis to alleviate the situation.

In addition to banks’ capital buffers, macroprudential policy includes so-called borrower-based measures. Almost all European countries have adopted several borrower-based measures into their regulations. In Finland, only a maximum loan-to-value ratio, so-called loan cap, is in place. Both the European Systemic Risk Board (ESBR) and most recently the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have recommended that tools to contain lending should also be adopted in Finland. The IMF's recent statement on Finland notes that the growing household indebtedness increases the need to enhance the macroprudential toolkit by new borrower-based instruments.

The FIN-FSA Board has voiced its concern on several occasions about households’ over-indebtedness in connection with the publication of its macroprudential decisions. Through its recommendation issued in December 2021, to be specified further in the first half of 2022, the Board's aim is to contain, even more strongly than previously, the excessive growth of household indebtedness. In granting credit, it is also important to consider potential changes in total debt-servicing costs. The loan applicant's debt-servicing capacity should not be compromised by an increase in interest rates or a disruption in the repayment of debt by the loan applicant1.

Need for borrower-based measures

Towards the end of 2019, the working group on excessive household indebtedness, established by the Ministry of Finance, completed its proposal. Based on the proposal, a Government bill is being prepared and will be submitted for consideration by the Government in late spring 2022. The draft Government bill on measures to curb indebtedness does not include the so-called debt-to-income (DTI) ratio or other income-linked instruments to restrict lending. The DTI would limit a borrower's loan-to-income ratio to a predetermined maximum amount.

Other potential instruments to limit indebtedness could include a cap on the loan amount relative to income (LTI, Loan to Income), debt servicing costs to income (DSTI, Debt Service to Income) or loan servicing costs to income (LSTI, Loan Service to Income). In establishing any restrictive instruments, the definition of debt, loans and income in more detail is naturally important. Unlike prudential requirements for financial institutions, borrower-based measures have not been defined or harmonised in European Union legislation.

Household debt and the definition of when it becomes excessive from the perspective of an individual person or the economy as a whole is a complex issue. Problems stemming from excessive indebtedness are best prevented by curbing borrowing, and this is the very purpose of macroprudential measures aimed at borrowers.

It is important that authorities at their disposal have an adequately versatile macroprudential toolkit. The existence of regulatory tools does not automatically mean these tools will be used. The implementation of new tools is always preceded by exact specification and thorough preparation. Consumer protection considerations pertaining to indebtedness must also be taken into account. High indebtedness hinders the resolution of potential crises or major problems affecting the economy or the banking sector. The conclusion of many studies is that the most longstanding impacts of financial crises are concerned with household debt, where housing loans play the single most important factor. Finland also has a need for new macroprudential tools to curb household indebtedness.

1 The FIN-FSA regulations and guidelines 4/2018 “Management of credit risk and assessment of creditworthiness by supervised entities in the financial sector” provide that, in the calculation of available funds, the interest rate should be set at least at six per cent and the maturity of the loan at no more than 25 years. The calculation of available funds should also reflect a potential increase in the financial charge for the housing company loan in the event of a rise in interest rates and the termination of any grace period for principal repayment. The regulations and guidelines apply to the management of supervised entities’ credit risk, but the relevant restrictions are also closely linked to the objectives of macroprudential policy.